In this series we discover more about the local heroes behind Knightsbridge’s many blue plaques

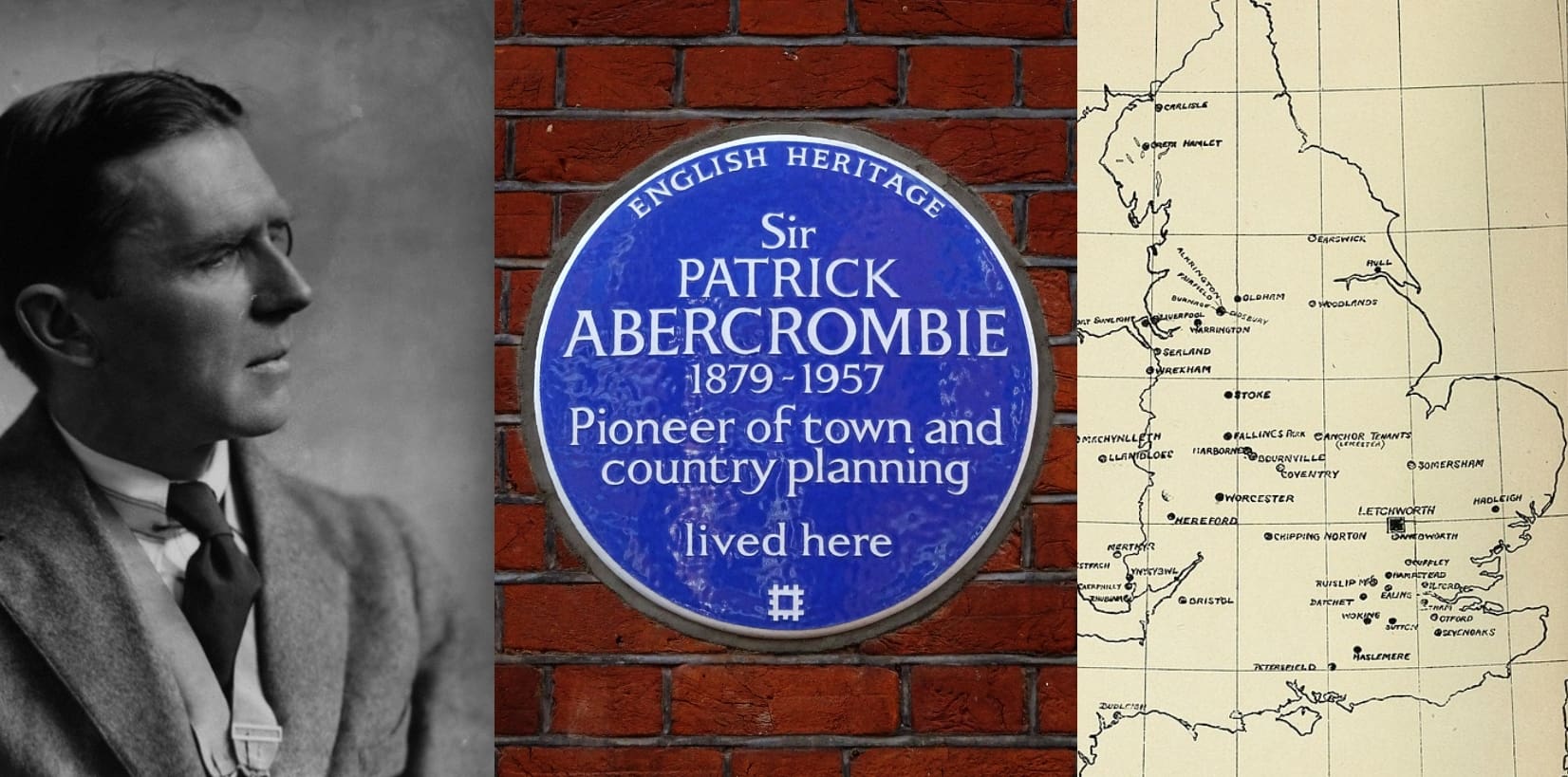

Blue plaque spotlight: Sir Patrick Abercrombie (1879-1957)

Who?

Sir Patrick Abercrombie: architect, town planner, professor of civic design at Liverpool University, professor of town planning at University College London

Where?

Flat 1, 63 Egerton Gardens, Brompton

Sir Leslie Patrick Abercrombie was born in circumstances conducive to a life of pioneering. His parents, Sarah and William, were a stockbroker and businessman, respectively. They were also both artistically minded; his father was a patron of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Morris.

Abercrombie enjoyed a good education under the tutelage of architect Charles Heathcote at the Manchester School of Art, before working as an apprentice to Arnold Thornley in Liverpool. He climbed the academic ladder and was appointed professor of civic design at the University of Liverpool in 1915.

One year earlier, he had won a competition held by the Civic Institute of Ireland by submitting a planning proposal that aimed to reform Dublin’s poor housing conditions. Many of the solutions Abercrombie suggested went on to influence the Dublin Reconstruction Act (1924), which set about rebuilding those parts of the Irish Free State’s capital ravaged by the Irish Civil War.

During the 1920s and 30s, Abercrombie became a respected authority on town planning and the garden city movement, which promoted the establishment of satellite communities comprising industry and agriculture in equal measure

He became professor of town planning at University College London in 1935, moving into Flat 1, 63 Egerton Gardens in Brompton, Knightsbridge. During the eight years he lived here, he would complete his most important work, which was in part a response to the devastation caused by the Blitz.

Marking its advent, German planes led a sudden two-hour assault on London on 7 September 1940. From churches to hospitals, the eight-month bombing campaign obliterated buildings of every description. One in six Londoners were rendered homeless, with over a million properties damaged or destroyed. Properties were desecrated right by Abercrombie’s residence at Egerton Gardens, as well as many others throughout Knightsbridge and Belgravia. Between Rutland Mews East and Rutland Street, there is a reminder of the past in the form of the “Hole in the Wall”. Historically, a boundary wall (thought to date back to the 1850s) divided Hyde Park and Knightsbridge, with the two areas inaccessible save for a tiresome detour. A bomb destroyed the wall during the Blitz, inadvertently creating a much longed-for path for locals. This unique slice of history is commemorated today by its own special plaque reading: “This boundary wall of the Rutland Estate was destroyed by a bomb, during World War II, on 25 September 1940. At the request of residents a right of way was established when the wall was rebuilt by the City of Westminster in 1948 and has come to be known as ‘the hole in the wall’.”

Though lives were being destroyed along with the city’s architecture, the British continued opening their shops and getting on with life in between German raids. During the previous world war, stores like Harrods had erected signs bearing the famous slogan, “Business as usual”. This was now adopted once more, with people chalking it onto operating premises and crumbling ruins alike.

In the wake of the Blitz, Abercrombie would improve the strained morale of the British public by pioneering the post-war reconstruction plans for London and its surroundings for which he is best remembered. His influential books, County of London Plan (1943) and Greater London Plan (1944), were collectively named ‘the Abercrombie plan’. In 1946, the Ministry of Information presented an overview of them in the short film The Proud City: A Plan for London, in which the narrator introduces Abercrombie as the ‘world-famous British authority on town planning’.

London was a sprawling morass of factories, housing and churches. Many people lived miles away from the nearest open space, as well as their workplace. As hundreds of thousands of evacuees began returning to London, it exacerbated a housing shortage. Abercrombie sought to redevelop the capital such that light, air, space and better living conditions would become available to all, while diminishing the wasted time suffered by commuters. All such aims were indicative of the pro-social attitude that underpinned his lifetime’s body of work. Among his many proposed changes was for ring roads around Greater London, which would ultimately lead to the development of the M25.

Abercrombie was appointed a Knight Bachelor in 1945 by King George VI, going on to be one of the few, including the likes of Mahatma Gandhi, to have multiple English Heritage blue plaques commemorating him (a second can be found in Aston Tirrold, the village where he lived after 1945).

In 1948, he became the inaugural president of the International Union of Architects and won the AIA (American Institute of Architecture) Gold Medal two years later. Today, a building is named after him at Oxford Brookes University, home to its Faculty of Technology, Design and Environment.