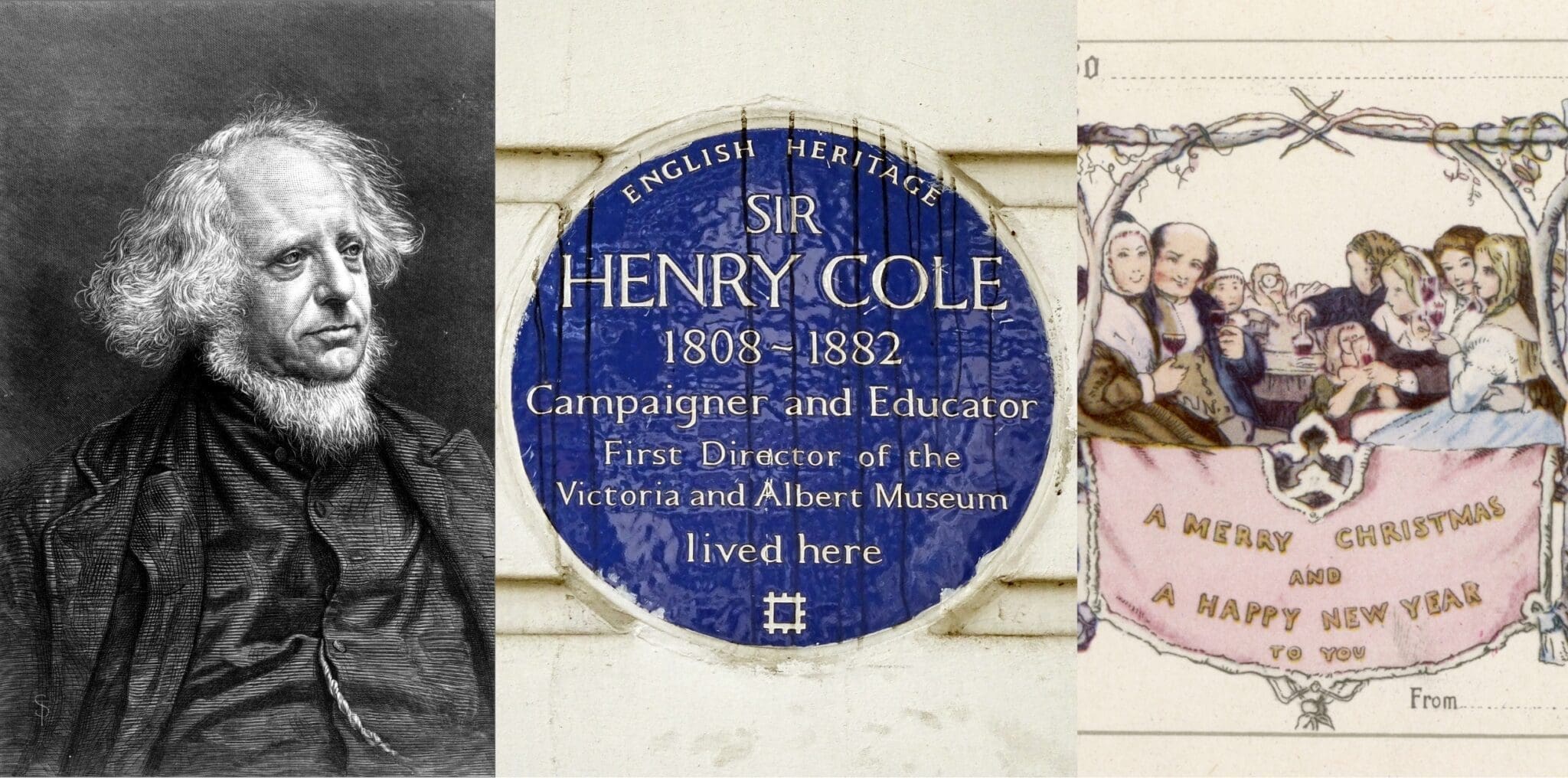

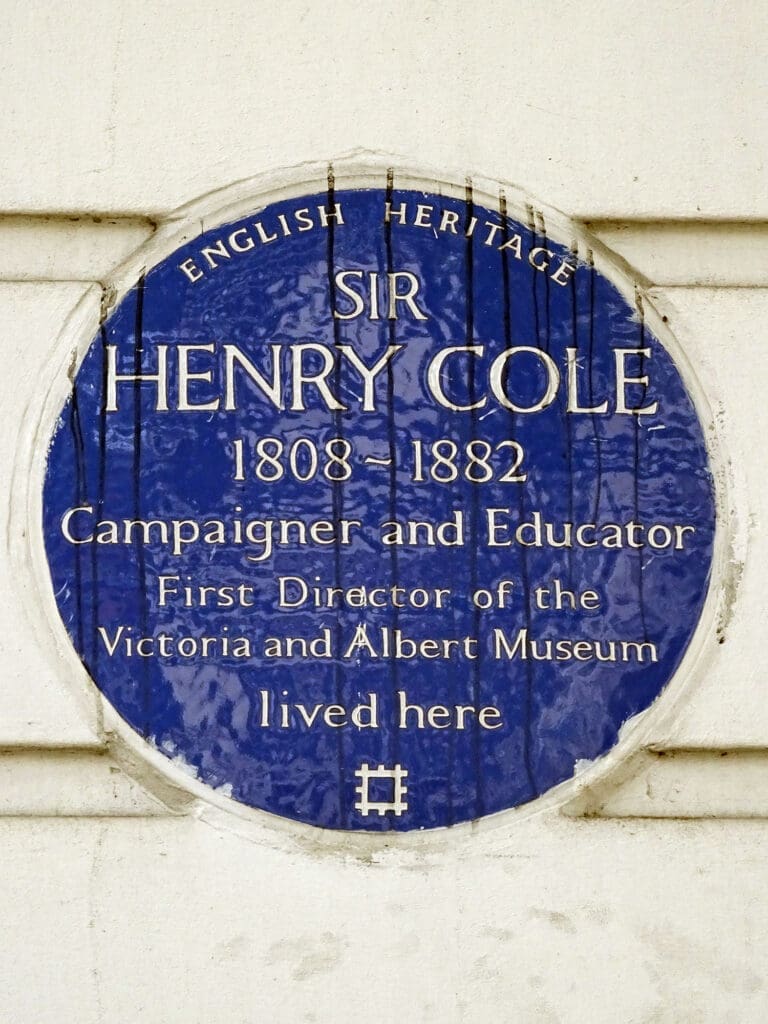

In this series we discover more about the local heroes behind Knightsbridge’s many blue plaques. This time we focus on Sir Henry Cole.

Blue plaque spotlight: Sir Henry Cole (1808-1882)

WHO?

Civil servant, reformer of public records and the postal service, founder of the Victoria and Albert Museum, inventor of the Christmas card, designer, children’s author

WHERE?

33 Thurloe Square, South Kensington, the site of the Embassy of Kazakhstan before 2013. The house is just opposite the façade of the V&A Museum in Knightsbridge

In 1833, Cole began working as a sub-commissioner for a Record Commission, the sixth Royal Commission (public inquiry) there had been into the state archives, which were disorganised and stored in poor conditions. The Commission itself received a tide of criticism from its employees, for its corruption and inefficiency, to which Cole was more than willing to contribute after being fired in 1835. Participating in the polemical campaign against his former employer helped him back into employment when it led to the establishment of a new record office under the Public Record Office Act (1838).

In the late 1830s, Cole also began to work as an assistant to Rowland Hill, helping him reform Britain’s postal system. At the time, the cost of sending letters was determined by distance and number of sheets. Sending anything was too expensive for most people. When they did, it was almost customary to save money by cross-writing – that is, writing two lines of text over each other at right angles on one side of the page. The price of postage was paid by the recipient, which led to another problem: a mix of paid and unpaid letters that created confusion in the postal service.

Cole’s employer proposed comprehensive solutions, the first being a fixed price irrespective of distance for letters up to a specified weight limit. Another was the introduction of prepayment, which could be marked with stamps, a suggestion Hill borrowed from the publisher Charles Knight. While Cole had proven instrumental in reforming the civil service’s record office, now he was fixing the country’s postal service by helping Hill organise the Uniform Penny Post and the creation of the Penny Black, the world’s first adhesive postage stamp.

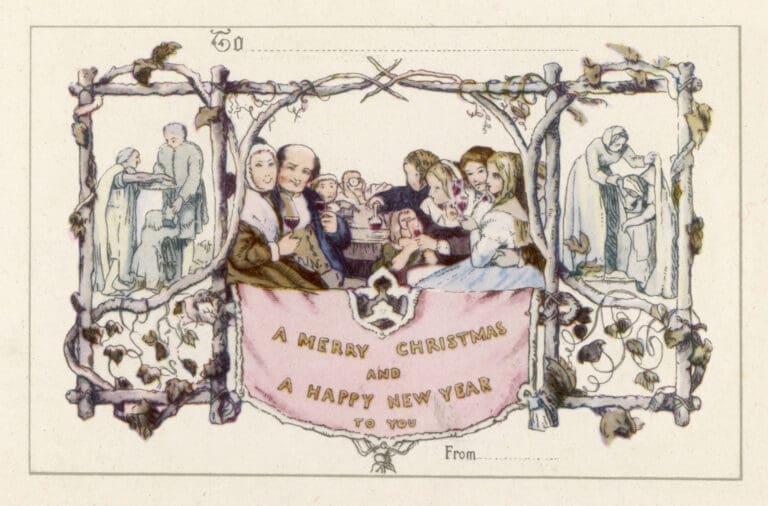

His involvement in major inventions didn’t end there, however. In 1843, Cole commissioned his friend John Callcott Horsley to design a festive greeting card that he could send to all his relations. Thus, the first Christmas card was born. It depicted three generations of Cole’s family raising a toast, with its margins showing people giving alms. In 2001, one of these cards was sold at auction for £22,500. Although 1,000 were originally made, very few remain in existence.

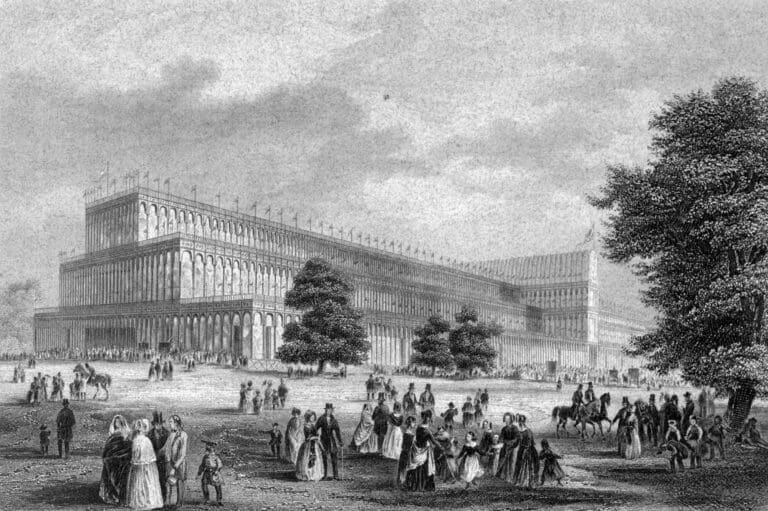

By now it shouldn’t come as a surprise that, despite his humble beginnings, Cole’s social circle became as elite as it gets. He knew Prince Albert through his membership to the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, of which the Prince Consort was president. In the late 1840s, Cole persuaded him to organise what transpired to be the most influential cultural event of the 19th century anywhere in the world. The 1851 Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, which took place in Hyde Park, showcased manufacturing from many countries, providing a great deal of inspiration for British designers. The world’s first international fair dedicated to industry and culture, it exhibited over a million objects and drew in crowds so substantial that they included a third of the British population.

The Great Exhibition generated a vast profit of £186,000 which Prince Albert directed towards creating a cultural area around Exhibition Road, which people dubbed “Albertopolis”. Now known as South Kensington, it became the home of institutions including the Royal Albert Hall, the Natural History Museum, and the V&A. Indeed, objects purchased from The Great Exhibition with a government grant were used in a seminal display for the Museum of Manufactures, which opened in 1852 with Cole as its first director. Following a couple of name changes, this would become the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1899, where today you can visit the Henry Cole Wing. And Cole’s old house is just across the road from the entrance.

With creativity to spare, Cole also wrote children’s books and designed objects under his pseudonym, Felix Summerly. In 1845, the Society of Arts announced a competition into which Cole entered Summerly’s tea service, manufactured by the Staffordshire porcelain company Minton & Co, and his business Felix Summerly’s Art-Manufactures opened in 1847.

Apparently revolutionary in everything at which he tried his hand, it’s hardly surprising Cole inspired Prince Albert’s witticism, ‘We must have steam, get Cole,’ or that in 1875 Queen Victoria knighted him.

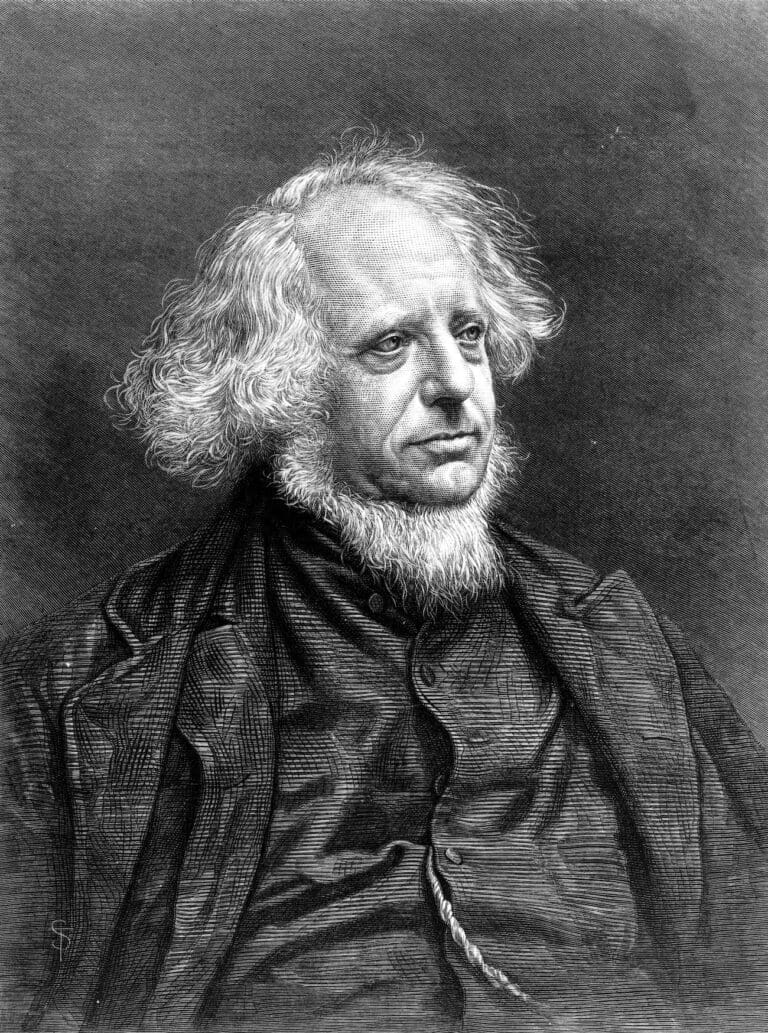

In April 1882, Cole sat for a portrait with renowned painter James McNeill Whistler, then died the following night. Yet he is immortalised through so many facets of British life taken for granted today, not to mention the fact that this exemplary Briton appeared in ITV’s 2016-19 period drama, Victoria, portrayed by David Newman.