In this series we discover more about the local heroes behind Knightsbridge’s many blue plaques. This time we focus on Elisabeth Welch.

Blue plaque spotlight: Elisabeth Welch (1904-2003)

WHO?

Singer, cabaret artiste, actor, and the first Black broadcaster to have her own BBC radio series

WHERE?

Flat 1, Ovington Court, just off Brompton Road

CLAIM TO FAME

Elisabeth Welch was born in New York in 1904. Her father was of African-American and Native American heritage, and her mother of Scottish and Irish. Throughout her life, this mixed descent would be reflected in Welch’s status as a maverick and free-thinker.

Her family were Baptist Christians, and it was in a church choir that she began honing her seemingly God-given gift: her velvety yet commanding voice.

After her 1922 stage debut in Black musical-comedy Liza, she starred in the musical Runnin’ Wild, which featured Cecil Mack and Jimmy Johnson’s lyricised version of The Charleston, the iconic jazz-age tune. Welch loathed the lyrics in spite of such profundities as:

Charleston, Charleston, gee how you can shuffle;

Every step you do, leads to something new.

Man I’m telling you, it’s a lapazoo!

Throughout the 1920s, Welch starred in a variety of shows on Broadway. At the end of the decade, she moved to Paris, where she began singing in cabarets. She met sex workers there for whom she had a great deal of empathy, as they were trying to provide for their children.

Fortuitously, Welch soon returned home to star in the hit musical The New Yorkers, performing Cole Porter’s scandalous song, Love for Sale. With lyrics written from the perspective of a Prohibition-era woman selling her services, the song had been banned from radio, but Welch considered it tragic and impactful.

Welch replaced the original singer, Kathryn Crawford, in the musical. This was to appease the furore of the audiences, who deemed it an inappropriate role for a white actor. To further placate the mob, the setting of the song was also changed from Midtown Manhattan to the Cotton Club in Harlem. In spite of the racist and degrading environment in which Welch landed the part, and the fact she was one of the earliest Black actresses to integrate on Broadway with a white cast, she insisted on a classy portrayal of her new role and an elegant outfit that she had picked out. No was not an answer.

Porter subsequently invited Welch to London to perform in Nymph Errant. Arriving there in 1933, she moved into Ovington Court, Knightsbridge. She lived in Flat 1 while breaking into England’s musical theatre scene, where she’d have a career spanning six decades.

During this time, she introduced Harold Arlen’s famous torch song Stormy Weather to the British public at the Leicester Square Theatre; hers preceding renditions by music legends including Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald and Shirley Bassey.

She also became the first Black broadcaster to win her own BBC radio series, Soft Lights and Sweet Music, in 1934. And she began starring in movies. With humility, Welch accepted many minor roles throughout her acting career. In the early days, she often played singers, but would later portray more surprising characters such as her comedic turn as Mrs Wu in Revenge of the Pink Panther (1978).

There’s no doubt Welch won the hearts and minds (and ears) of the British public. She remained in London during the Blitz, entertaining the troops. She knew members of the royal family, occasionally singing at Buckingham Palace garden parties. And when she made her final public appearance in 1997, attending a tribute concert at the London Palladium for the theatre critic Jack Tinker, she received a standing ovation.

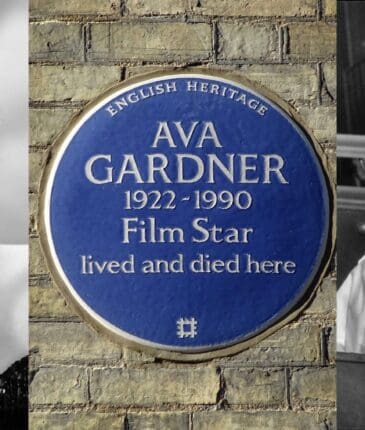

After Welch’s death in 2003, her biographer Stephen Bourne campaigned for a blue plaque to commemorate her. The plaque immortalises the extent to which one of Knightsbridge’s most inspirational residents is remembered and respected even two decades after her passing. It was unveiled in 2012 by the playwright and critic Bonnie Greer, who spoke of the quiet tenacity with which Welch had pursued her career. As Greer explained, ‘She presents another pathway, another option, she shows the way for any young Black woman, any woman, any person who wants to go their own way in life.’